EUREKA — If the American West represents the “geography of hope,” as author Wallace Stegner wrote, then what better place than California’s far north to illustrate the eternal tension between the limitless potential of big ideas and the brutal disappointment of broken dreams?

The Golden State’s verdant North Coast, a great empire of trees and home to the Yurok, the state’s largest Native American tribe, has seen centuries of boom and bust — riches taken from above and beneath the earth. When gold miners brought their nuggets from the foothills to the coast, Eureka’s broad bay became a bustling transit hub.

After the gold was gone, it was replaced with timber, “red gold.” The region’s massive redwoods made many locals rich; when the forests were clear cut, the pulp mills came. They, too, went bust. Dams harnessed the region’s rushing rivers to produce electricity, causing the collapse of its prized salmon runs. A “green” cannabis revolution arrived, promising to bring a balm to this depressed place. But a glut of legal weed flooded the market, leaving the plants to wither along with the growers’ dreams of wealth.

Now, once again, the siren call of capturing the North Coast’s natural resources beckons dreamers and speculators, this time the treasure lies far off the rugged coast of Humboldt and Del Norte counties. Its promise: The Pacific Ocean — which feeds us, modulates our weather and delivers our goods — will provide clean, renewable energy from its powerful winds.

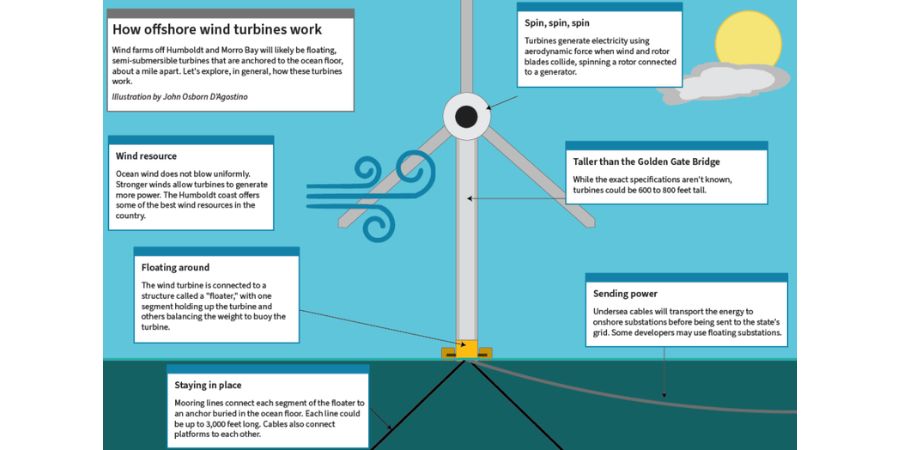

The tantalizing possibility of capturing wind energy from giant floating ocean platforms is considered essential to achieving California’s ambitious goal of electrifying its grid with 100% zero-carbon energy. The state’s blueprint envisions offshore wind farms producing 25 gigawatts of electricity by 2045, powering 25 million homes and providing about 13% of the power supply.

A new gold rush doesn’t begin to describe the urgency of harnessing wind off California when it comes to meeting climate goals. The first, substantial step has been taken: Last December, the federal government auctioned off 583 square miles of ocean waters off Humboldt Bay and the Central Coast’s Morro Bay to five energy companies — with more lease sales expected. The five wind farms will hold hundreds of giant turbines, each about 900 feet high, as tall as a 70-story building.

The projects will be a giant experiment: No other floating wind operations are in such deep waters. From China to Rhode Island, about 250 offshore wind farms are operating around the world, mostly in shallow waters close to shore and secured to the ocean floor. But the areas off California with the strongest winds are far from shore and too deep for traditional platforms, so developers are planning clusters of floating platforms about 20 miles off the coast, in waters more than a half-mile deep and tethered by cables.

The depth, distance from shore and new floating technology drive up the costs and complicate an already expansive process. Massive infusions of private and public money will be needed. And it likely will be a decade or longer before any major wind farms off California begin to produce power: The companies will spend up to five years preparing technical plans and analyzing environmental impacts of each project. Then federal and state review and permitting could take two or more years, and construction could last five or more years.

Sign up for the CREATE Newsletter and stay updated on the latest information in Renewable Energy Education.